A pioneering NASA robot detected over a thousand quakes on Mars. It also may have revealed a huge reservoir of water.

Planetary scientists used unprecedented data collected by the space agency’s InSight lander, which recorded geologic activity on Mars for four years, to reveal that water may exist many miles down in the Martian crust. The research, which invites further investigation, may explain where bounties of the Red Planet’s water went as the world dried up, and suggests that Mars may host hospitable environs for life.

On our rocky planet, bounties of water exist in the subsurface. Why not on Mars, too?

“Exactly! We identified the Martian equivalent of deep groundwater on Earth,” Michael Manga, a planetary scientist at UC Berkeley who coauthored the new research, told Mashable.

The study recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The detected water is nowhere near the Martian surface — which is today 1,000 times drier than the driest desert on Earth. It exists some seven to 13 miles underground (11.5 to 20 kilometers) in cracks and ruptures in the deep Mars crust, as shown in the graphic below.

Mashable Light Speed

NASA designed the InSight lander to observe Mars’ inner workings, so the craft carried a seismometer, similar to those that measure quakes on Earth. It picked up different types of seismic waves, caused by marsquakes, geologic activity, and meteorites bombarding the surface. Crucially, these waves, which are generated by an impulse like an impact or temblor, provide lots of information about the world below. The speed of a seismic wave depends on what the rock is made of, whether this rock has cracks, and what the cracks are filled with, Manga explained. The researchers then plug these seismic Martian readings (along with subsurface gravity measurements) into programs that simulate what lies below — they’re the same computer models geologists use to map water aquifers on Earth or gas resources deep underground.

“A mid-crust whose rocks are cracked and filled with liquid water best explains both seismic and gravity data,” Manga said.

A graphic showing pockets of water deep inside the Martian crust.

Credit: James Tuttle Keane / Aaron Rodriquez

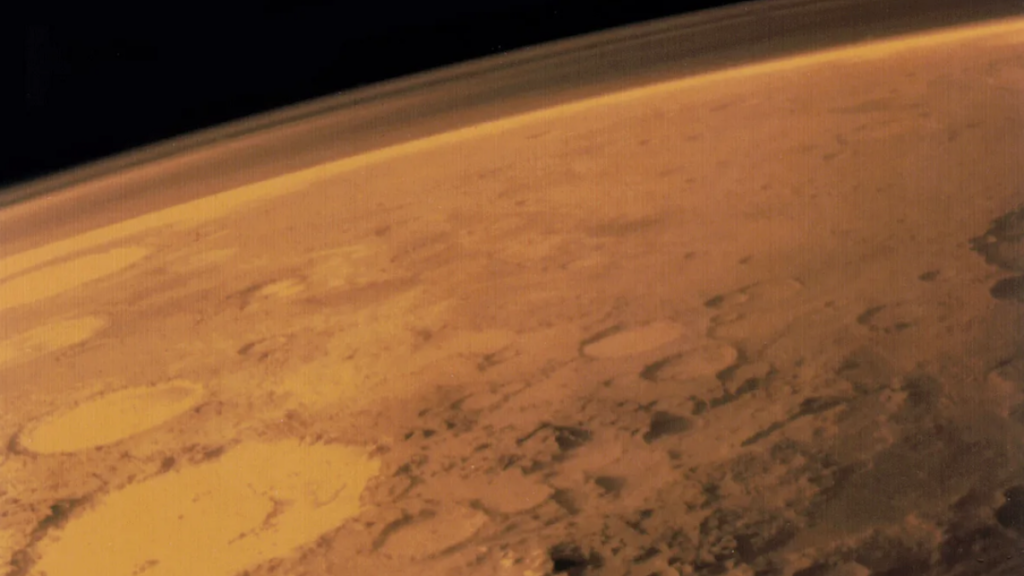

A view of the InSight lander’s dust-covered seismometer on the Martian surface.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

A temperate Red Planet once hosted great Martian lakes and rivers. Some 3 billion years ago, scientists suspect much of this water was lost to space after Mars gradually lost its insulating atmosphere. Yet colossal amounts of water might have drained into the subsurface, too. It’s unclear how much, though this latest water detection suggests a considerable amount of water could lie in the deep Martian crust.

“We knew that the liquid water being buried deep in the subsurface was one possible solution to the question of where Mars’ ancient liquid surface water went,” Manga said.

“On Earth we find microbial life deep underground where rocks are saturated with water and there is an energy source.”

The possible existence of water raises an enticing question. Could something live down there? Our planet provides a clue.

“On Earth we find microbial life deep underground where rocks are saturated with water and there is an energy source,” Manga said.

Future Martian explorers won’t be able to drill many miles into Martian rock to access or analyze this water. But they might find other places, such as geologically active regions like Cerberus Fossae on Mars, where liquid water could potentially be expelled to the desert floor.

The Martian surface may indeed be a harsh, irradiated place, but it’s plausible hardy life could thrive in the deep, watery underworld.