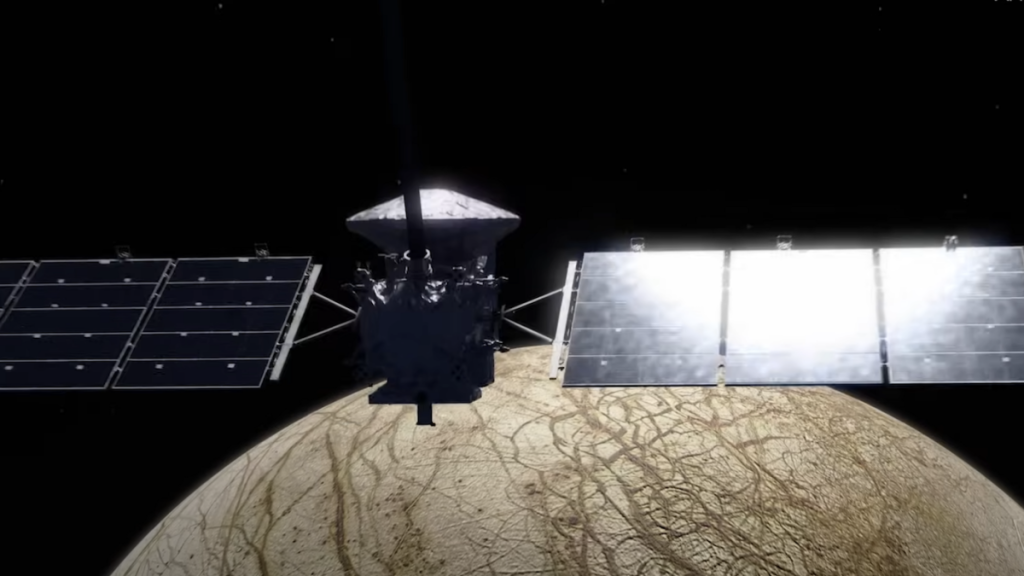

A NASA probe, the length of a basketball court, is headed to the tantalizing world Europa.

Planetary scientists are confident this moon of Jupiter harbors a deep ocean. A looming question is whether it hosts the ingredients and conditions to support life. With around 50 close flybys of the planet, the sizable craft — the largest probe NASA has ever built for a planetary science mission — intends to find Europa’s answer.

“It’s perhaps one of the best places beyond Earth to look for life in our solar system,” Cynthia Phillips, a NASA planetary geologist and project staff scientist for the space agency’s Europa Clipper mission, told Mashable.

The mission’s launch opportunity window opens soon, on Oct. 10, where it will blast off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. If NASA finds that Europa is a habitable world, a second Europa mission will return, this time landing there to see if it’s inhabited.

A graphic comparing the size of the Europa Clipper spacecraft to a basketball court.

Credit: NASA

Why the Europa Clipper spacecraft is so big

Europa Clipper, over 100 feet (30.5 meters) long, is big because it needs to generate solar power in deep space. And the Jupiter region only receives three to four percent of the sunlight that Earth receives. Hence the long wings, or arrays.

“You just need these giant solar arrays in order to power all your instruments,” Phillips explained. “We’re talking about a huge expanse of solar arrays.”

Capturing loads of the distant sunlight will create some 700 watts of electricity, which is “about what a small microwave oven or a coffee maker needs to operate,” NASA explains. But the craft also carries batteries to help power a host of moon-sleuthing instruments.

“I’m really excited about this payload that we’re bringing to Europa,” Phillips said.

“I’m really excited about this payload that we’re bringing to Europa.”

An ice-penetrating radar will look beneath the moon’s icy, cracked crust. It will see how this icy subsurface is composed, and possibly, possibly, detect where the ice meets the ocean. (Europa’s ice shell is likely some 10 to 15 miles, or 15 to 25 kilometers, thick.) This radar could detect about half a mile deep, or it could be much more — that depends on how fractured the ice is and the purity of the ice (a fractured subsurface, for example, means the radar signal will bounce around more, as opposed to penetrating down). There’s potential, however, that the radar will infiltrate a whopping 19 miles (30 kilometers) down.

One of Europa Clipper’s wings extended at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Credit: NASA

The Europa Clipper’s SUrface Dust Analyzer, or SUDA, which will scoop up particles blasted into space around the moon.

Credit: NASA / CU Boulder / Glenn Asakawa

In addition to a suite of specialized cameras, Europa Clipper also carries an instrument called the SUrface Dust Analyzer, or SUDA, that will literally sample particles of Europa that have been ejected into space by tiny meteorites. “Micrometeorites constantly blast fragments of Europa’s surface into space,” NASA explains. “The ejecta are individually small, but scientists estimate that half a ton (about 500 kilograms) of Europa’s surface material floats above the moon at all times.”

Mashable Light Speed

One of the most exciting opportunities of the mission — though far from guaranteed — is the craft potentially flying through a water-ice plume blasted out from Europa’s surface. This would allow the instruments exquisite insight into Europa’s interior.

“We would love to fly through a plume,” Curt Niebur, Europa Clipper’s program scientist, said at a press conference leading up to the mission’s launch.

“We would love to fly through a plume.”

Plumes or not, mission scientists believe that some 50 close flybys of the surface will provide ample observations to prove whether or not Europa could harbor life. Sure, it almost certainly has water. But all life needs energy: Does this ocean world provide an energy source? And does it harbor the basic chemical ingredients, like carbon, to form the building blocks of life as we know it?

And, if all those conditions are satisfied, is there evidence the ocean has been around for billions of years, providing a stable environment for life to evolve and sustain itself in Europa’s dark sea?

Why scientists think Europa has an ocean

The Europa Clipper mission is an expensive science endeavor, costing some $5 billion. But NASA is confident this Jovian moon harbors an intriguing sea perhaps twice the volume of all Earth’s seas.

Why?

“It’s a great detective story,” Phillips said.

“It’s a great detective story.”

In 1979, the Voyager 2 spacecraft captured the first detailed views of Europa, showing a surface dominated by crisscrossing cracks. And many of these lines were reddish, suggesting that something below the surface welled up to fill them. Planetary scientists also knew that as Europa swings by the gravitationally powerful gas giant Jupiter, its interior gets stretched and pulled, a process that produces heat on a world. This tugging could have provided heat on Europa for billions of years.

“This made Europa really, really interesting,” Phillips noted.

An artist’s conception of the ocean, and geothermal energy sources, that could exist beneath Europa’s thick ice crust.

Credit: NASA

Europa’s surface as captured by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft.

Credit: NASA

Then, in the 1990s, NASA’s Galileo mission captured legendary views of Europa’s chaotic, ridged surface — suggesting there was water near the top. What’s more, the spacecraft detected a strong magnetic signal from the moon. Saltwater, a really good magnetic conductor, could have provided this signal.

“Galileo showed Europa was even more interesting than suspected,” Phillip said.

“It’s a great detective story.”

The evidence only mounted. On multiple occasions, the Hubble Space Telescope spotted evidence that plumes of water erupted 125 miles (200 kilometers) above Europa’s surface. It all added up. “There is very likely a subsurface ocean on Europa,” Phillips said.

And if it’s remained somewhat stable for many eons, it could harbor conditions suitable for life to develop. We won’t know, until we get there in 2030.

“This is a voyage into the unknown,” said Nicola Fox, who heads NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.